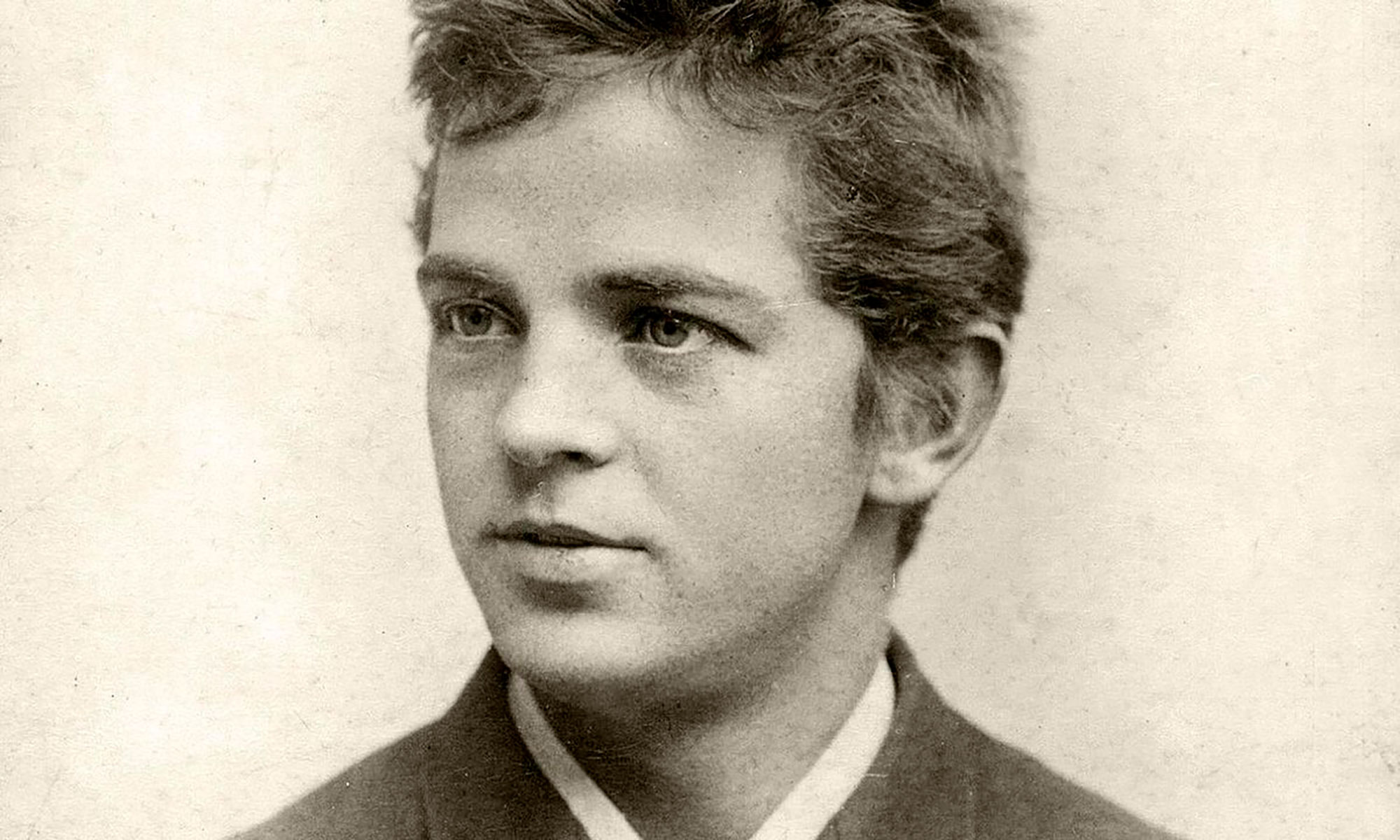

Young and promising

Carl Nielsen’s major subject at the Conservatory of Music was the violin, but by the end of his education at the very latest his fellow-students must have realised that composition was his real interest. His official debut as a composer took place after he had left the Conservatory, in the Tivoli Concert Hall on 17 September 1887, where his Andante tranquillo e Scherzo for string orchestra was performed (with himself playing the violin in the orchestra)

Shortly after this he was again noticed as a composer when the Private Chamber Music Society (whose concerts were called “meetings” and as such were not open to the general public) performed his newly composed String Quartet in F major on 25 January 1888.

On 8 September 1888, the orchestra of the Tivoli Concert Hall gave the first performance of Carl Nielsen’s official opus 1, the Suite for Strings, with a week’s delay compared with the original programming because a now long-forgotten English composer took the young Dane’s music off the bill in favour of two of his own works. Balduin Dahl conducted, and he almost dragged Carl Nielsen from the violinists’ group to receive the audience’s ovation. The success was so great that the second movement, a seductive waltz, had to be repeated and afterwards Carl Nielsen went out with his friends to celebrate.

On 16 October the same year Carl Nielsen personally conducted this same piece at the first concert of the season in the Odense Music Society – his debut as conductor. Nielsen would surely have been happy to appear free of charge, but he actually received a fee of 30 crowns.

At the beginning of 1890 the work was printed and published by Wilhelm Hansen. Recent research in connection with the new critical edition of Carl Nielsen’s works has revealed that in the meantime Nielsen had made alterations in the suite, especially in the third movement. At the end of May 1889 Dahl had given Nielsen permission to conduct the suite himself in Tivoli, and this was his conductor’s debut in Copenhagen.

In August 1889 a competition took place for vacancies in the Chapel Royal Orchestra. Carl Nielsen won a place, and from the start of the 1889-90 season he was among the second violins in the orchestra. In those days it was customary to let newly appointed violinists begin as second violins, and in the course of his 16 years as a Chapel Royal musician Nielsen never made it higher than to the first desk of the seconds. It was probably not his intention to play in the orchestra so long. His talent as a violinist did not extend further than a few opportunities as a soloist at the so-called popular concerts, but on the other hand it was not possible for him to make a living by composing.

Among his colleagues at the Chapel Royal were three outstanding oboists, Chr. Schiemann, Peter Brøndum and Olivo Krause. The last two of these became close friends of Nielsen, and he was inspired to write his two Fantasy Pieces for Oboe og Piano, opus 2. Krause (1857-1927) was to have performed both pieces for the first time at one of the Chapel’s chamber music soirées in December 1890, but he was taken ill so that the two works were published by Wilhelm Hansen before Krause and Victor Bendix eventually gave them their christening at the next soirée on 16 March 1891.

Although on paper he was fully trained as a musician, Carl Nielsen knew that as a composer he needed to acquire more knowledge and to widen his horizons. Being badly off economically, he had to resort to the few scholarships that the cultural life of that time could provide. One of the opportunities available was the Ancker Award (Det Ancker’ske Legat), founded with money bequeathed by rentier Carl Andreas Ancker (1828-57).

With leave from the Chapel Royal for the whole season of 1890-91, and with funding from the Ancker Award, Carl Nielsen set out for Germany. While at home he had procured recommendations from Niels W. Gade, with whom he had spent a whole day at his home in Fredensborg. This was to be his last meeting with the old master. In Dresden he attended in September the four operas in Wagner’s Ring, which made a strong impression on him: “the musician who does not think Wagner great is himself very small” – a point of view which he was later to modify rather severely. After a trip to Leipzig Nielsen departed on 18 October for Berlin, where he continued to attend concerts and operas diligently. Among other musical colleagues he met composers Jean Sibelius and Christian Sinding and the famous German violinist Joseph Joachim, who agreed to listen to Nielsen’s newly composed String Quartet in F minor.

On 22 December Carl Nielsen received the news that Gade had died the day before. He writes in his diary: “Darkness and emptiness! Terrible! I am sick with sorrow and can neither eat nor sleep.”

In the following months Nielsen divided his time between Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden, where he looked out for the most interesting concerts and operas. Among other things he attended Johan Svendsen’s Carnival in Paris in Berlin (“the most daring piece of music Svendsen has written”), and in Dresden he heard Victor Bendix’s First Symphony (“a great and well-deserved success”). And at the end of January he left for Paris.